Common Deficiencies

Updated November 25, 2025

All Levels

- ACS or PTS familiarity: If you enter a checkride (or mock checkride) and don’t have a thorough understanding of the ACS (or PTS) testing document for the test you are taking, you are already on your way toward failure. These FAA documents spell out the requirements for practical tests. Yes, you heard that right, the FAA spells out exactly what will be included on your exam! Please make sure to take some time and review the ACS or PTS document for your test. Here’s a link to the Airman Certification Standards and Practical Test Standards on the FAA’s website.

- ACS or PTS checklists: Showing up without a required item (such as a nav log or flight plan form) can be basis for failure. The FAA has published a standalone ACS Companion Guide with a checklist for ACS-based tests on Page 19. For PTS-based tests, the checklist is included in the relevant PTS.

- The “perpetually open” open book: Though FAA checkrides are “open book” and applicants are allowed to refer to FAA reference materials during a checkride, an applicant who is frequently consulting books is not entirely prepared. Here’s one DPE perspective: “No Googling Allowed: Checkrides are the Ultimate Open-Book Test.” Russ Still over at Gold Seal has written an article, “Open-Book Checkrides – Are They Real?” that’s also worth a look.

- EFBs: The FAA has finally entered the digital age and has explicitly allowed the use of electronic reference material on checkrides (you did read the checklist above, right?) as of May 2024. However, applicants using ForeFlight, Garmin Pilot, or other EFBs in lieu of paper reference materials are not exempt from ACS testing requirements! If you choose to use an EFB, you should know how to use all of its functions. The week prior to a checkride is *not* the time to be learning a new EFB software.

- Aircraft records: Are you absolutely sure your aircraft is airworthy and appropriate for the checkride? You’d be surprised how many times applicants provide an aircraft that is for one reason or another, not checkride-ready. This means that the aircraft has all required inspections for the intended use (e.g., don’t show up for a checkride at a towered airport with an expired 91.413 transponder inspection) AND has all updated and correct paperwork (AROW). Don’t forget things like records of GPS updates and VOR checks if you plan to use these to navigate. Although they are not legally required to be current while operating Part 91 under VFR, it’s good practice to be able to show that you have considered this aspect of your navigation plan.

Private Pilot, Sport Pilot

As the Private Pilot and Sport Pilot certificates are both entry-level pilot certificates, they share common failure points.

- Weather information: Regardless of the weather source you use for your briefing (call, online, EFB), be prepared to talk about your process of understanding the weather picture. A good preflight briefing starts with a big-picture understanding of the weather in the flight area (air masses, fronts, etc.), and gets more granular from there. You need to be able to demonstrate to your examiner that you can identify and avoid areas of hazardous weather. What prompts the issuance of AIRMETs and SIGMETs, and what bearing do they have on you as a pilot of a small aircraft? Once enroute, how do you plan to get weather updates? What are the limitations of various enroute weather sources (ADS-B, FSS, etc.)? Where might you go to find information on weather products if you forgot a symbol on a Surface Analysis Chart or couldn’t remember a particular METAR or TAF abbreviation?

- Cross-country planning: Create your flight plan in the way that you would if you were flying it as a real-world flight and be prepared to justify your routing decisions. Be able to describe the fuel requirements for the flight, both the amount needed to make the flight as planned as well as the legal (and practical) reserves required. Think about contingencies too; what happens if a headwind is stronger than forecast? Have you flight-planned in the opportunity for an alternate or fuel stop? What DO all those symbols on the chart mean? If you don’t know one, where can you find out what it signifies? What all is in the Chart Supplement, and what do you need to know about an airport you plan to visit?

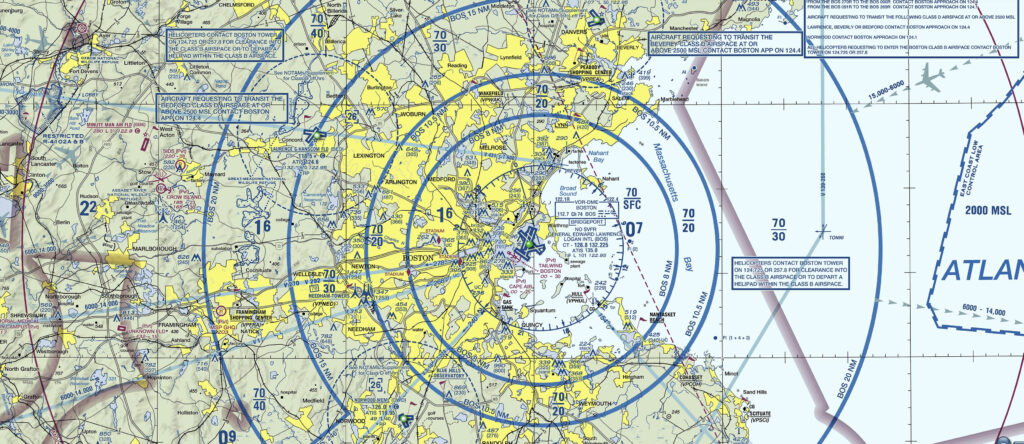

- Airspace, airspace, airspace: Most applicants are actually fairly good with Class airspace (perhaps because of the emphasis it gets during ground school). Oftentimes, though, special use airspace (MOA, R-, P-, etc.) cause issues, especially for those who have not directly experienced flying around it. Your certificate grants you permission to fly anywhere in the United States, so you’ll need to be prepared for any type of airspace you may encounter. This applies for quasi-airspace too, such as wildlife refuges and wilderness areas that may have altitude restrictions or altitude suggestions. Be able to identify the airspace along the proposed cross-country route. If your flight plan takes you into busy airspace, know the equipment and communications requirements for entry, and be ready to discuss the communications sequence you will use to enter the airspace. Oh, and VFR cloud clearance and visibility minimums, of course.

- Aerodynamics: Don’t be surprised to be asked a few questions about the basics of flight and aerodynamics. At the private level, you’re expected to have sufficient knowledge of how the aircraft works to be able to operate it safely. Yes, you know that an airplane turns when you “bank and yank,” but what forces are involved here?

- Minimums: Basic VFR weather minimums are important; but so are other minimums…minimum safe altitudes (in different locations), minimum fuel reserves required…

- Airworthiness requirements: Be able to quickly locate and explain recent maintenance entries, including but not limited to annual inspections, 100-hour inspections, and AD compliance. What can you as a certificated pilot do in terms of maintenance? Can you change oil? Wheel bearings? An instrument in the panel?

- Operation of systems (and common failure modes): You don’t need to know your systems like a mechanic, but you do need to be able to describe the basics to demonstrate that you understand how they function, and how they fail. System specifics vary from airplane to airplane; be ready to describe any system that is needed for flight in your airplane. For example, what does your aircraft’s electrical system look like? What does the alternator do? How many volts does it produce? What happens if it fails and stops outputting? How much reserve power do you have? Can you reset the alternator? How many times will you try? Etc.

- Weight and balance: Make sure you have the most current weight and balance for your airplane and that it correctly reflects the equipment installed. If you rely on an EFB to do your weight and balance calculations, the data used must match the actual weight and balance for your airplane. Using the default profile for your aircraft make and model (and not the actual W&B data for your aircraft) is grounds for checkride failure.

- EFBs: Speaking of EFBs… If you want to use an EFB on your checkride, be prepared to demonstrate mastery of the device and its functions. Be prepared to do things like make changes to fuel and passenger loading (for W&B), explain the fuel burn calculated by the EFB, demonstrate your ability to add an intermediate stop on your flight plan, etc.

- Performance: As noted above, your certificate gives you license to go anywhere and everywhere, even places you shouldn’t. If the cross-country scenario presented would put you in a place where your aircraft’s performance does not provide an acceptable margin of safety, say so!

- Stall and spin awareness: Be ready to discuss stalls and spins, including what causes them and the places where they most commonly occur (and are most dangerous). What is the recommended spin recovery procedure?

- Sport Pilot limitations and endorsements (Sport Pilot only): The Sport certificate is a great pathway to get in the air, especially where a Private certificate isn’t an option. However, it does come with some restrictions. Be prepared to discuss the additional limitations placed on a Sport Pilot, as well as how you might be able to get some limitations removed (e.g., flight into Class D airspace). LSAs also have slightly different maintenance paperwork requirements. Know what the LSA equivalent to an AD is.

Commercial Pilot

A Commercial Pilot is held to higher standards than a Private Pilot. In addition to demonstrating flying experience and flying skills above and beyond those required for Private, the Commercial Pilot is expected to have additional depth and breadth of knowledge. You’ll see many of the same subjects on your Commercial as you saw on your Private, but they will be covered in more detail.

- Simple to complex: In the Commercial, applicants tend to want to demonstrate that they have acquired advanced knowledge and are oftentimes overeager to demonstrate this during a checkride. When responding to examiner prompts, start with simple explanations to show a solid understanding of the basics. Then, if prompted, explain in detail.

- Operation of systems: This is a great example of where additional depth of knowledge is required. At the Private level, one may have been able to describe the fuel system of an airplane in a single sentence, e.g., “Two tanks in the wings, gravity feed to the carburetor.” That’s a great starting point (simple!) for the Commercial level, but if the examiner asks for more, you’ll need to know about the venting system, the cross-linkage between the tanks, the routing of the fuel lines, etc. Walk through the path fuel takes from the tank to the power stroke of the engine. Why does this particular airplane have “unusable fuel?” Is it ever possible to use that?

- Aircraft familiarity: It is fairly common for a Commercial applicant to be flying an aircraft for a Commercial checkride that they do not have much experience in. You will be responsible for knowing the aircraft’s systems, whether you have 1 or 1,000 hours in the particular make and model! Several years back, the FAA eliminated the requirement for Commercial checkrides to be done in a complex aircraft. Take advantage of this and fly the airplane you are most comfortable with!

- Complex / TAA systems: If you’re bringing a complex and/or TAA aircraft to your Commercial checkride, be prepared for questions about how these systems work! Electronic flight instruments don’t always work the way their analog counterparts do. You’ll need to be able to explain how these instruments obtain data to display, as well as their failure modes. Even if you’re not bringing a complex aircraft, you can be asked about complex aircraft systems in general – as you may eventually be flying one as a Commercial Pilot. The constant-speed propeller gives many candidates trouble.

- Pressurization, oxygen, and high-altitude flight: A Commercial Pilot will be expected to know not just when oxygen is legally required, but also the different types of oxygen systems, how to brief passengers on their use, and the consequences of lack of oxygen. This isn’t just “hypoxia happens,” but how long it takes one to lose consciousness at varying altitudes, etc. When is a high-altitude endorsement required? How do you get one? How do pressurization systems work (or worse…not work)?

- En-route weather and en-route weather information: Be able to describe some of the common methods for obtaining en-route weather, as well as the dangers that certain en-route weather products may present (lag, accuracy, etc.). These may have been covered in your Private Pilot and/or Instrument Rating training, but expect them to show up again here (recall also that not all Commercial Pilots have an Instrument Rating).

- Required equipment: Yet another topic where a Commercial Pilot will have a greater depth and breadth of understanding than a Private Pilot. Be ready to describe MMELs, MELs (and how to get one), KOELs, as well as standard equipment requirements under a variety of complex scenarios.

- Airworthiness: In primary training, most pilots fly the same make and model (and often the same N-number) regularly. As a Commercial Pilot, you may be flying different makes and models frequently. You’ll need to be able to explain how to examine maintenance records quickly and effectively to determine the airworthiness of an aircraft. And, of course, not all aircraft you fly will be “by the book” – you’ll need to know about STCs, Type Certificates, and other items necessary to determine if a (modified) aircraft continues to be airworthy by meeting its its Type Design.

- Airspace, airspace, airspace (again): In addition to needing to know your standard airspace, you’ll need to know rules that might affect larger aircraft that a Commercial Pilot might be flying (speed limits, etc.). The Commercial ACS also calls out several types of Special Use Airspace. Expect to discuss operations in a SFRA, SATR, ADIZ, NSA, etc.

- Emergency equipment and survival gear: What is legally required (in a given scenario, usually involving over-water flight)? What is not legally mandated but good practice?

- Commercial operations: Many ground schools heavily emphasize this aspect of the Commercial certificate, but it’s still important that you know the privileges and limitations of the certificate and the medical status required to exercise those privileges. You should also be very familiar with the concept of holding out, air charter, and how to determine where an operation falls in the eyes of the FAA. Know AC 120-12A well!

- Avionics: As with any system, a Commercial Pilot needs to know the workings of the avionics onboard their airplane. Expect questions about the operations of specific installed avionics, their limitations, and failure modes.

Flight Instructor

The above-listed knowledge deficiencies certainly can carry forward to the CFI checkride if the candidate does not have a solid basis of knowledge. After all, to effectively teach a subject, you must first know it yourself! However, the biggest issues we see with CFI candidates are (in order of frequency):

- Endorsements and Logbook Entries: With your new CFI certificate, you’ll be a guide for clients of all levels, ranging from the zero-hour, zero-knowledge student as well as the experienced pilot wanting to add additional qualifications. Instructors must be able to outline the training and endorsements required for various scenarios, including clients seeking initial certificates, additional certificates, flight reviews, and additional aircraft privileges. It’s also imperative that instructor candidates understand what must be logged, how it is logged, and where it must be logged.

- Effective teaching: The flight instructor’s job is to deliver knowledge to their student(s) in a professional, efficient manner tailored to the needs of that individual student. Many initial instructor candidates are well-prepared from a knowledge standpoint, but lack the ability to transfer this knowledge on to the next generation of pilots. Often, CFI candidates struggle with brevity and summation of complex topics. For these candidates, lessons/presentations turn into a stream of consciousness of “all the things I know about (topic) versus a structured explanation that works from the simple to the complex.

- Inability to apply Fundamentals of Instruction (FOI) to real-world instructing scenarios: The FAA emphasizes that all instructor candidates without prior formal teaching experience must become familiar with the Fundamentals of Instruction from the FAA’s Aviation Instructor’s Handbook. Some candidates have done an excellent job memorizing FOI terminology and structure in preparation for their written exams, but don’t understand how these principles are applied in a real-world instructional environment. In day-to-day flight instructing, you won’t be asked to draw out and itemize the six levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain. However, you will want to understand that a student’s grasp of a particular topic is not a yes/no binary; there are different levels to how well a topic has been learned.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

One of the best ways to verify you are ready for your checkride (and won’t make some of these common mistakes) is to take a comprehensive mock checkride with us. Click below to book an appointment.