Checkride Prep Guide

Updated October 10, 2025

You’ve completed all of your aeronautical experience requirements and your written exam. Now it’s on to the Practical Test (checkride)… but how do you prepare? You’re in luck! This guide provides a free, step-by-step outline to preparing for your primary certificate (Private Pilot, Sport Pilot) oral exam. If you’re less than a day out from your checkride, you’ll want to refer to 24 Hours Before Your Checkride.

The FAA ACS is the outline of your upcoming Practical Test. Yes, you read that correctly, the FAA tells you exactly what you’ll be tested on! The ACS should be your primary study guide throughout your checkride preparation.

Simply put, if you are knowledgeable on the Tasks and Elements in the ACS, and can apply them to real-world scenarios, you’ll be ready for the oral exam portion of your checkride.

The resources given here are for the Private Pilot level, but the process will serve you well for any FAA certificate or rating you might seek. If you’re looking for Commercial Pilot prep resources, check out our Commercial Pilot Checkride Prep Resources.

Studying With the ACS

We encourage all candidates to do at least one line-by-line review of the ACS during their checkride preparation. Naturally, you’ll need a copy of the ACS. You can download a free copy or purchase a printed copy.

- Private Pilot ACS – printed copy

- Private Pilot ACS – download

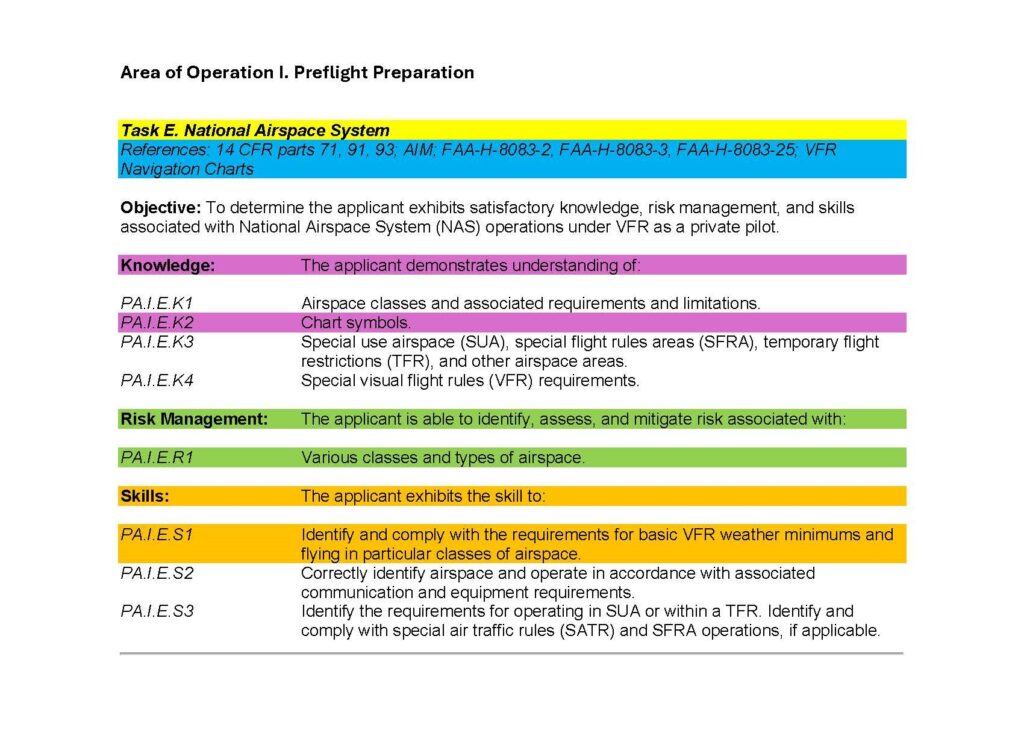

Let’s examine an ACS Task, ACS Task I. E., “National Airspace System” to see how to use the ACS to guide your studying.

At the top of each Task, the FAA provides us a set of References. For the Task of “National Airspace System,” these include 14 CFR parts 71, 91, 93; AIM; FAA-H-8083-2, FAA-H-8083-3, FAA-H-8083-25; VFR Navigation Charts. You can find the 14 CFR items in your FAR/AIM or online at ecfr.gov. FAA-H-8083-2 is the FAA Risk Management Handbook. FAA-H-8083-3 is the Airplane Flying Handbook. FAA-H-8083-25 is the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge. VFR Navigation Charts refers to VFR sectional charts.

You’ll find that Tasks are broken down into Elements. Elements are either Knowledge Elements, Risk Management Elements, or Skill Elements.

One Knowledge Element is “Chart symbols.” To study for this Element, you will want to pull out a VFR sectional chart and quiz yourself (or have a study partner quiz you) on symbols you encounter on the chart. Use the chart legend or the FAA Chart User’s Guide to verify you’re correct.

The FAA also wants applicants to be familiar with Risk Management Elements. For this Task, you should be able to describe the risks you might encounter in “Various classes and types of airspace.” You might ask questions like “What risks are present in an active Military Operations Area (MOA), and how can I mitigate against these risks in my preflight planning?” You could consult the FAA Risk Management Handbook if you need more information on how to identify and mitigate against risks.

Skills require candidates to apply their knowledge to scenarios provided by the examiner. An example is to “Identify and comply with the requirements for basic VFR weather minimums and flying in particular classes of airspace.” Again, ask yourself questions like “Along this particular flight route, I might encounter multiple types of airspace. I see I will be in Class E, Class C, and Class B. At this particular point, I will be in Class E airspace. What are the required VFR cloud clearances and visibility minimums in this airspace?”

If you find that you want to explore an Element further, first consider reviewing the References listed in the ACS, then revisit your notes from ground school and/or one of the many supplementary resources listed below.

FAA Reference Material

The checkride is an open-book test, so take advantage of this! Most people prefer printed copies of FAA reference materials, but searchable digital copies are acceptable. PDFs can be downloaded from the FAA website. You’re not expected to memorize these front to back, but you will want to be familiar with each volume and where to find information you may need. At minimum, you’ll want a copy of the FAR/AIM, the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK), and the Airplane Flying Handbook (AFH).

The ASA FAR/AIMs contain a section (pictured at the top of this page) which gives relevant FAR/AIM sections to study for a given certificate. This can be used as a supplement to the ACS outline.

If you choose to bring a printed copy of the FAR/AIM, many people find it useful to add colored tabs (or to purchase a pre-tabbed version) to help locate information quickly. Tabbing is not required but it does show a level of preparedness that many examiners appreciate.

- 2025 FAR/AIM – printed copy

- 2025 FAR/AIM tab kit – rather than buying an (expensive) pre-tabbed copy, pay $19.99 and put the tabs in yourself.

- 2025 FAR/AIM pre-tabbed – if price is no object.

- FAA Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, Revision C – printed copy – note that not all Amazon copies are full-color. This one is.

- FAA Airplane Flying Handbook, Revision C – printed copy – full color.

- FAA Risk Management Handbook – printed copy

- FAA Aviation Weather Handbook – printed copy

Your Ground School and Your CFI

Commercially produced online ground schools represent the combined effort of numerous instructors, and are designed to package up difficult material in an easy-to-understand format. Online ground schools provide the prerequisite aeronautical knowledge you’ll need to pass your written; and (most of) the knowledge that is covered in the checkride. Take advantage of this and revisit your ground school material to help reinforce your knowledge of ACS Tasks and Elements you’re having a tough time with. Some ground schools, such as Sporty’s, include checkride prep modules. If your ground school includes this, give it a try and see if it is helpful for your studies.

We do not currently recommend any standalone checkride-prep specific online packages. These are typically videos with an “examiner” and a “student” discussing ACS topics; these sorts of videos are available for free elsewhere.

Your CFI should be a resource for you during your preparation. They’re a familiar, trusted voice and they know how you learn best. They are also uniquely positioned to offer you in-person training. Sometimes, all it takes to grasp a topic is to connect it to a concrete, real-world example. Struggling with maintenance requirements? Ask your CFI to sit down with you and your airplane’s logbooks and go through the required inspections, maintenance entries, AD lists, etc.

Some instructors are not inclined to provide ground instruction; leaving it up to the candidate to “figure out” the knowledge needed for the checkride. If this is the case for you, we offer one-on-one ground instruction if our schedule allows. Please contact us to schedule a session.

Checkride Prep Books

- Private Pilot Oral Exam Guide (Jason Blair) – be sure to get the updated 14th edition, released June 5, 2025.

- Private Pilot Checkride Preparation and Study Guide (Virgil Royer)

Checkride Prep Podcasts / Audio

Long drive coming up? Put on one of these audio streams! Podcasts are a great way to get “in tune” with the material you may encounter during your checkride oral.

- The VSL Aviation Podcast: DPE Thoughts on the ACS – DPE Seth Lake breaks down the ACS (in the same manner we have done above) and explains how an examiner uses the ACS to administer a checkride. This series consists of several episodes.

- Mock Private Pilot Checkride with DPE Jason Blair – DPE Jason Blair gives a mock checkride to podcast host Max Trescott. Max is already a certificated pilot and flight instructor, so his answers are more prompt and accurate than those of the average candidate!

- On Centerline Podcast with Sam Tarrel – Sam Tarrel, a.k.a. Northwest Aeronaut, has assembled a comprehensive series on the Private Pilot ACS. He does an excellent job explaining the ACS point-by-point, as well as tying in to real-world flying examples. Look for the ACS Breakdown episodes.

- FAA handbooks on Audible – The FAA Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge and Airplane Flying Handbook are available on Audible. Although the audio format removes some important illustrations and diagrams, they are still a useful listen. Note that these are the -B versions; the current version is -C. There are only minor differences in organization between the versions.

- Rod Machado’s Private/Commercial Pilot Handbook – Rod Machado’s humor is unique, and you’ll either love or hate it. If you’re partial to dad jokes and silly puns, you’ll want to check out his material. Rod Machado’s Private/Commercial Pilot handbook is available in audiobook format. You’ll probably want to purchase both the audio book and the PDF copy so you can view the illustrations and diagrams.

- Pass Your Private Pilot Checkride – Jason Schappert of MzeroA is another instructor who elicits strong reactions (both positive and negative) from students. The book spans about two and a half hours of audio; not enough to comprehensively cover the entire ACS. However, he does provide some useful test-taking strategies and highlights several areas which examiners often emphasize.

Mock Checkride Videos

We feel like the best checkride prep videos are those which demonstrate the checkride process from start to finish, with minimal editorializing from the “examiner” and a maximum amount of Q&A with an actual certificate candidate. The best are made by actual examiners and/or CFIs with decades of experience preparing candidates for checkrides.

DPE Todd Shellnut has partnered with Gold Seal to make an excellent series of mock checkride videos. You can see candidates at different levels of readiness; and, in some cases, see how a DPE may navigate an exam with a candidate who has less-than-perfect knowledge.

- Gold Seal Private Pilot Mock Checkride No. 1 – A reasonably well-prepared candidate, Steven.

- Gold Seal Private Pilot Mock Checkride No. 2 – A candidate with some gaps in knowledge, Mike.

- Gold Seal Private Pilot Mock Checkride No. 3 – A candidate still several weeks out from checkride, who needs significant work between now and then, David.

A few more that we feel provide an accurate portrayal of a Private Pilot checkride:

- Allan Englehardt Gives a Private Pilot Checkride – An oldie-but-goodie; a candidate faces a very straightforward examiner, and gives good responses throughout.

- Mary Latimer Gives a Private Pilot Mock Checkride – A mock checkride given by Mary Latimer, a former DPE, to a candidate, Megan, who does a good job of answering most questions. The examiner, Mary, presents several scenarios and a range of questions ranging from very simple to quite complex. The only downside of this video is that the examiner did not conduct a thorough debrief with the candidate.

- King Schools offers paid videos. We have found these to be of similar quality to the free videos listed above. If you are already a King Schools subscriber, they’re worth a look.

Here, it seems appropriate to say a few words about “mock checkride” videos filmed by just any old CFI, especially low-experience CFIs posting numerous videos looking for social media clout. There are dozens of such videos on YouTube, etc. where the “exam” isn’t an exam at all. Rather, it’s the “examiner” (low-experience CFI) bouncing from topic to topic, teaching some, rambling some, and flipping through the aircraft POH looking for “questions” to ask of the student. When the student gets a question wrong, the CFI steps in immediately to correct. Remember, this is a low-experience CFI doing the teaching; the “correction” provided may not be correct at all.

FAA ASIs and DPEs have cohesive, scenario-based Plans of Action for each test they administer. A good test flows seamlessly from one topic to the next, and looks more like a conversation than an exam. Examiners are not allowed to teach during test administration, and most examiners choose not to provide feedback or corrections during the exam. If you expect your examiner to correct your mistakes and teach you if/when you stumble, you’re setting yourself up for failure because this isn’t how FAA checkrides work. Practicing/studying with this unrealistic type of “mock checkride” video is not an effective use of your study time (at best) and can contain inaccurate or even dangerous information (at worst).

Passively watching, taking notes, and learning from mock checkride videos like those linked above is a great way to enhance your feel for what checkrides may look like. However, they’re not a substitute for doing your own mock checkride (whether that’s with us or with another experienced instructor who didn’t participate in your training). Your level of preparedness for “the real thing” is highlighted when you’re the one having to answer questions!

Additional Materials

- Gold Seal Private Pilot Know-it-all – One of the best “cheat sheets” at the Private Pilot level comes from Gold Seal. It’s also free. Great if you learn well from bullet points. Use this in the same way you might use flash cards.

- Gold Seal Ultimate Infographics – Best used as a flash-card aid to help you commit important topics to memory. If you’re a visual learner, these may be for you.

- Pilot Institute Private Pilot Study Sheet – Pilot Institute is a well-known provider of ground schools. They offer their “Private Pilot Study Sheet.” It features visual aids to help you retain information, as well as bullet-point lists. Requires sign-up for download, but it’s free.

- Backseat Pilot ACS Review – Several candidates we’ve worked with have liked the content from Backseat Pilot. Their ACS Review is an expanded outline; more in-depth than the cheat sheet above. The cost is reasonable at $29.

- Answers to the ACS – Another resource that we’ve heard positive things about is the Answers to the ACS app by Patrick Mojsak. It’s a comprehensive app / eBook, with several hundred pages of content, breaking down each ACS task and element with incredible granularity. For detail-oriented students who want to have all possible knowledge at their fingertips, this is a good option. A demo version will allow you to see if this presentation works for you. The app is only available for Apple devices.

Create Your Checkride Binder

Each ACS has an applicant checklist which spells out the minimum items you must bring to your checkride. We strongly encourage candidates to create a checkride binder so these items are available in one spot for quick reference.

Your checkride binder should include the following sections:

- Candidate Documents: Photocopies of your photo ID, student certificate, medical certificate.

- Certificate Application: Application documents, including a printed copy of your IACRA form. A paper 8710-1 is not a bad idea, either. Make sure it is is properly signed by your instructor.

- Knowledge Test Report: Paper version, and endorsement indicating completion of knowledge deficiency review. Typically, this endorsement is written on the test report. If your instructor puts it in your logbook, make a copy of it and include it with the knowledge test report.

- Pilot Logbook Copies (optional): You are required to present your original logbook during the exam. Many students tab the appropriate sections for easy lookup. Making copies for the examiner to review is encouraged if your logbooks are electronic or difficult to decipher. You’ll want copies of logbook entries that demonstrate the required flights and hours to meet aeronautical experience requirements for the certificate you are seeking, as well as required endorsements. For Private Pilot, see 61.109.

- Navigation Logs and Flight Plan: Completed navigation logs and VFR flight plan form for the scenario assigned by your examiner. You do not need to file the VFR flight plan for your checkride.

- Preflight Briefing / Weather: Printed version of electronic preflight weather briefing or notes from call with FAA briefer. Don’t forget non-weather information like NOTAMs! You’re being asked to plan a flight in the same manner as you would in the real world, so make sure you get your briefing (or update your briefing) as close as possible to your checkride time. Make sure to update your nav log to include the most current winds aloft forecasts.

- Aircraft Documents and Maintenance Records Copies (optional): You are required to have access to the airplane’s documents and maintenance records during the checkride. Having photocopies of the required items in your binder can expedite this portion of the exam. Make copies of required documents, maintenance records, and inspections, e.g., AV1ATE items.

- Performance: Actual performance calculations should be made as part of your flight plan. You will want to bring your entire POH, but it’s not a bad idea to have copies of charts from your POH available for quick reference should your examiner ask you to calculate performance in an alternate scenario.

- Weight and Balance: Completed weight and balance sheet for your aircraft, reflecting the loading scenario provided by the examiner.

- Airport Diagrams, Charts/Chart Excerpts, Procedures: If your flight plan requires you to fly to any airports where an airport diagram is available, print one out for discussion and reference. This includes your home airport! Likewise, if your flight plan takes you into congested airspace or if the flight plan will require any special procedures (arrival, departure, etc.), have a copy of these for discussion or reference. Bring the checkride binder aboard the aircraft, too. Your iPad with ForeFlight may be sufficient for your oral, but inevitably, it will “fail” during the flight portion, so you’ll be glad you have paper backups!

- Personal Minimums List: Although you are not required to provide a written personal minimums list, it is likely that an examiner will ask about your personal minimums. Why not think about them beforehand and write them down?

- Examiner’s Fee: Check with your examiner to see what method of payment they prefer.

- Anything else your examiner requires: Some DPEs will ask you to fill out their own forms or checklists. If you’re asked to complete one of these, do so!

The “Taking Flight” YouTube channel has a good “How to Make a Checkride Binder” video.

Here’s another applicant’s checkride binder video. Her binder contains several items not mentioned above. Although none of these additional items are strictly necessary, it’s easy to tell that she has thought out what sort of questions her examiner might ask and has attempted to bring all the information she can to the checkride.

Answer Strategies

There’s no one “right” way to answer questions on a checkride, but you should consider your breadth and depth of knowledge about the topic, as well as any resources available, as you put your best answer forward. Here are five tips to help you craft the best possible answers on your upcoming checkride.

(Note: Answer Strategies have moved to their own page. Too much good stuff to fit here!)

Take a Mock Checkride

Okay, you’ve done your studying! Now, it’s time to verify your work with a mock checkride. That’s where we come in. We provide third-party mock checkrides to help you (and your instructor) assess whether you’re ready for your upcoming FAA Practical Test.

We suggest taking a mock checkride with an instructor other than your own primary instructor approximately 7 to 14 days prior to your scheduled checkride date. If you find you are deficient in some areas during the mock checkride, this buffer provides sufficient opportunity to brush up.

Students/candidates, here are ten reasons you should take a mock checkride.

Are you a CFI? Here’s some information for CFIs about why you should send your students to another instructor for a mock checkride.