Should I Buy an Airplane for Flight Training?

"I'm a low-time or zero-time student looking to buy an airplane to do my flight training. I heard that I can save some money if I do this and hire an independent CFI."

"Is that true?"

This is one of the most common questions asked on student pilot forums. Before I give my opinion, let me explain where I’m coming from. I’ve been a flight instructor for around a decade, and have been working for magazines that promote aircraft ownership since 2017. I’ve also owned aircraft outright myself, and been part of a club that owned and operated several aircraft.

Please understand that I’m not “anti-ownership” by any means. Ownership has a ton of (non-financial) benefits. Your aircraft will be exactly as you left it after your last flight. You’ll have zero worries about whether the previous renter fueled it or dinged something on landing. Your aircraft will be available to you whenever you want it. If you want to take it on a 14-day training/golf trip with your CFI aboard, go for it. No one else will have scheduling priority. If you want to personalize your airplane by changing the panel configuration, reupholstering the seats, painting the N-number a different color… you are the one to make that call.

But when it comes to the question of “Will I save money by owning rather than renting for training?” — generally, the answer is NO. Sometimes, that’s a “ABSOLUTELY NO.” Other times, depending on your circumstance, that’s a “well, maybe it will work out for you.” And there are numerous pitfalls that low-time students aren’t aware of that can make ownership inadvisable. Let me explain.

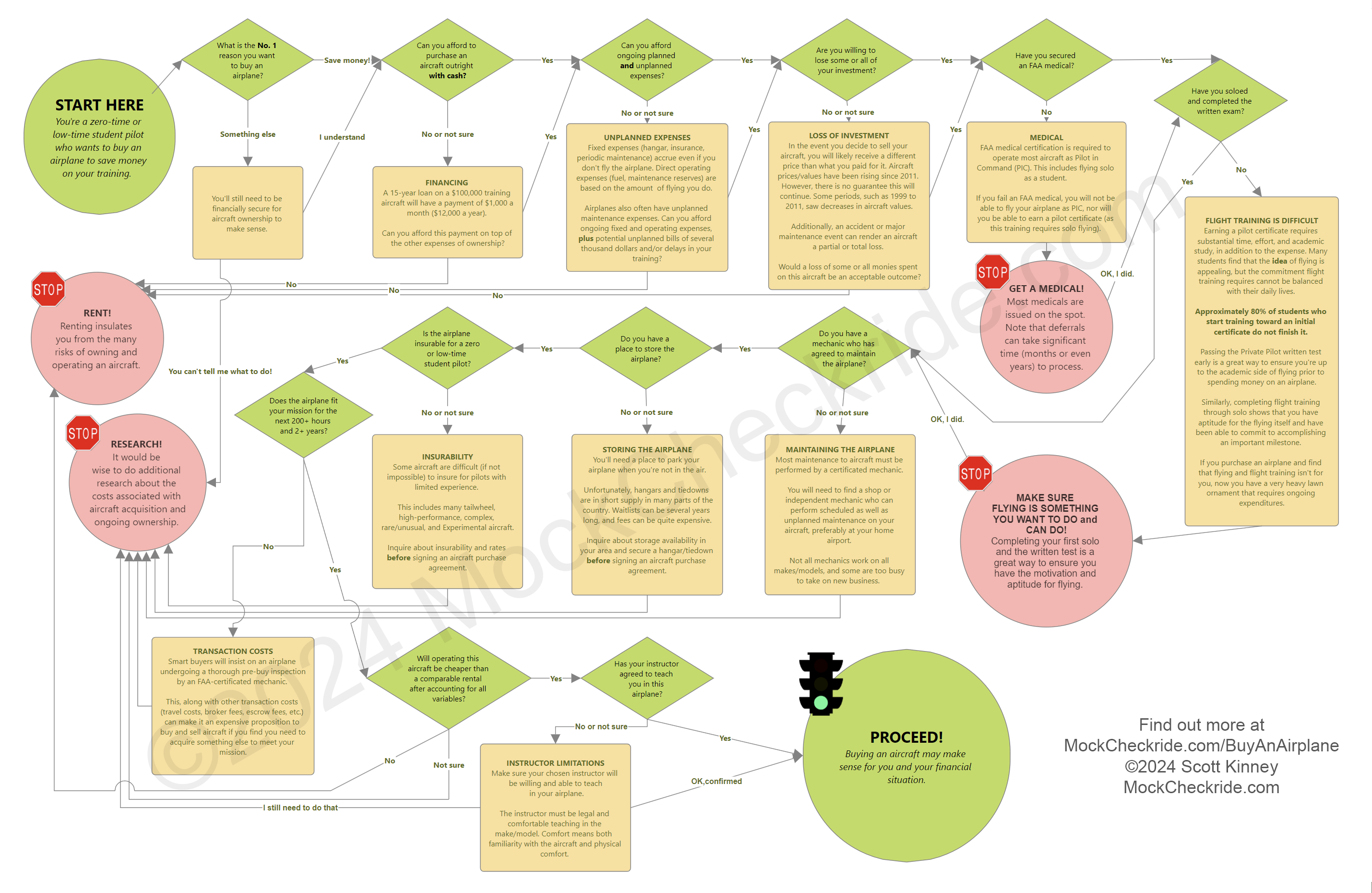

You can also skip right to our Student Pilot Aircraft Ownership flowchart.

Base Assumptions

For illustration, we’ll look at a scenario where a zero-time student pilot wants to buy a standard trainer aircraft. A basic Cessna 172 from the early-mid 1970s (172M model) is a very common choice. As of this writing (October 2024), a ballpark cost is around $100,000 for a reasonably well-equipped 172M. At this price point, you’re getting a four-seat aircraft, with a mid-time airframe, a mid-time engine, decent cosmetics, and an IFR-capable panel, perhaps with a GPS.

We’ll assume that you have zero hours, and you’re looking to complete your training through your Private Pilot certificate, and then, after some flying on your own, you’ll get your Instrument Rating. You plan to complete this training over the course of two years. Let’s assume it takes you the national average (75 hours total time, of which 50 hours is dual instruction) to earn your Private certificate, and then another 50 hours to earn your Instrument Rating (50 hours dual). You’ll fly an additional 75 hours solo, for a total of 200 hours of flight time, of which 100 hours will be dual instruction.

Renting

The following assumes an IFR-equipped Cessna 172 or similar airplane with a rental rate of $175/hour and a school instructor rate of $75/hour. You will also take out a non-owned insurance policy costing $800/year.

Item Cost Total

200 hours rental $175 / hour $35,000

100 hours instruction $90 / hour $9,000

100 hours solo no charge $0

Non-owned insurance $800 / year $1,600

Total $46,100

For the aircraft and instructor costs, you’ll be in for $46,100 for your first two years of flying.

Note that this summary is not intended to encompass all the costs of flight training. Other items, like headsets, ground schools, exam fees, will increase the total sum, but these are required regardless of whether you own the aircraft.

Owning

Now, let’s take a look at the costs for owning the same aircraft to see how much can be saved by owning.

For illustration, we’ll use an area of the country with average fixed costs. A hangar will be $200/month, insurance for a zero-time student will be $2,000/year (2% of hull value), and required annual and other inspections will run $2,000/year (inspections only; before any maintenance/repairs). This means you’ll be paying around $6,400 a year regardless of the hours you fly. Assume that you fly 100 hours a year, and that’s $64/hour for fixed costs.

We’ll also assume average operating costs; $40/hour for fuel and oil. You’ll also put aside some money for unplanned maintenance and your engine overhaul reserve fund; $50/hour. That’s $90/hour for operating costs.

Assuming 100 hours a year, you’ll be paying $154/hour to operate the airplane, a slight savings over renting. But there’s a bonus; as an owner, you’ll be paying tach hours (engine hours) versus Hobbs time. Tach hours convert to Hobbs hours at about a 1:1.3 rate. So that owned airplane costing $154 per tach hour is around $119 per Hobbs hour.

Additionally, independent instruction is usually around $15-20 per hour cheaper than instruction through a school.

Item Cost Total

200 hours operating costs + reserves $119 $23,800

100 hours instruction $75 / hour $7,500

100 hours solo no charge $0

Total $31,300

For the aircraft and instructor costs, you’ll be in for $31,300 for your first two years of flying… of course, this doesn’t account for the $100k you spent on the aircraft!

Not So Fast!

On the surface, owning does indeed seem to be a better idea than renting. You’ll save $14,800 over the course of your training. Right? Well, maybe. Please keep reading.

Paying Cash Versus Financing

Many people will look into financing some or all of the purchase price. A 15-year loan on $100,000 at 8.75% interest means a payment of $1,000 a month, or $12,000 a year ($24,000 in payments over our two-year timeline).

Part of the loan payment will be applied to principal, but after two years, you’ll still owe $93,000 on the aircraft. You will have paid some $17,000 in interest. And you’ll need to have the cash flow to cover a $1,000/month payment.

Item Cost Total

200 hours operating costs + reserves $119 / hour $23,800

100 hours instruction $75 / hour $7,500

100 hours solo no charge $0

Loan payments $1,000 /month $24,000

Payment toward principal $7,000 – $7,000

Total $48,300

Hmm. So it’s obviously better to pay cash if you have it, right? Well, yes. But any money spent on an asset like an airplane isn’t going to be invested elsewhere. Stock markets have been returning 20%+ on a year over year basis, but we’ll use a more conservative 6% for the cost of money.

Item Cost Total

200 hours operating costs + reserves $119 / hour $23,800

100 hours instruction $75 / hour $7,500

100 hours solo no charge $0

Cost of money 6% or $6,000 / year $12,000

Total $43,300

Double hmm. Even if you pay all cash, you’re not saving much now (only $2,800 in this example – $46,100 for renting, $43,300 for owning) versus a pay-as-you go rental. If the assumed cost of money goes up to 7.5%, now you’re not saving anything at all.

Airplanes Break. A Lot.

Read this section carefully as it’s the most important reason that you should be wary of buying an airplane to save money during your flight training.

Airplanes used for training are generally quite old. The Cessna 172M in our example is pushing 50 years old. Training aircraft have a rough life — rather than spending several hours at a time cruising from destination to destination, training aircraft take off and land, take off and land, take off and… well, sort of land, if you could call that a landing. Students are rough on training aircraft, and you will be rough on yours as a student, too. Ugly landings and maneuvers are part of learning to fly.

In the training environment (and outside it too, if we’re honest), airplanes break. A lot. Far more than you can ever imagine.

“But,” you say, “I’ve been a responsible owner and I’ve put away $50/hour for maintenance reserves!”

When major maintenance expenses occur or the engine needs overhaul, you’ll be ready with…$5,000 in the bank after the first year; $10,000 in the bank after Year Two of ownership. Should be plenty, right?

Let’s look at some costs for a few common maintenance items (these include remove/replace labor from a certificated mechanic) on a Cessna 172:

Landing gear tire: $250-$500

Overhauled gyro instrument: $600-$1,500

Replacement radio: $2,000-$6,000

Replacement WAAS GPS: $10,000-$25,000

Overhaul fuel sending unit: $800

Overhaul or replace alternator: $1,000-$2,000

Replacement exhaust: $5,000

Overhaul propeller: $800-$2,500

Replacement propeller: $6,000

Single cylinder: $1,500-$2,500

Top overhaul: $6,000-15,000

Overhauled engine: $40,000 (yes, really. https://www.airpowerinc.com/henpl-rt9947)

New engine: $80,000 (https://www.airpowerinc.com/enpl-rt9947)

And so on and so forth (there are several thousand parts on any given Cessna 172, and each and every one can need to be replaced). Go to an aviation supply house (e.g., Aircraft Spruce & Specialty) and price out parts; they’re many, many times more expensive than what you’re used to from other machines. While a vintage automotive alternator might cost $200, a replacement alternator for your old Cessna will cost $1,279 (https://www.aircraftspruce.com/catalog/eppages/lightweight_alternator.php), plus several hundred dollars labor to install.

Assume that you have just a few minor unplanned maintenance items crop up in that first year of ownership. You can see how that $5,000 a year can evaporate quickly…very quickly.

Now, what if you’re the one holding the bag when the engine kicks the bucket after only 10 hours of flight training? You’ll have $500 in maintenance reserves, leaving you to come up with tens of thousands of dollars just to restore the airplane to flying shape. This has happened to a few friends of mine; they ended up dropping $50,000 on a complete overhaul prior to doing any substantial flying of their aircraft. Had they bought these airplanes with the goal of saving a couple thousand dollars in training… well, let’s hope they’re training for the next 2,000 hours, because that’s about how long it will take to get back to break-even after suffering a $50,000 unplanned expense.

It’s possible that you won’t experience any of these items during your course of ownership. However, you shouldn’t count on it. Talk with some aircraft owners and ask them how much unplanned maintenance they’ve had to do in the past 200 hours. You may be surprised.

A wise owner will always ensure they’re able to pay for a repair above and beyond what’s in the maintenance reserve fund. If you can’t pay for a repair, the airplane now becomes a money drain (you’ll still be paying fixed costs) as it sits and collects dust.

Ensure that you have the ability to pay for repairs above and beyond what’s in your maintenance reserve fund.

Good Help is Hard to Find

MAINTENANCE: General Aviation has a shortage of qualified mechanics willing and able to work on standard single-engine aircraft. It’s tough to get scheduled maintenance done (annuals, other inspections); and even more challenging if it’s an immediate-need situation. Many maintenance shops are several months out in scheduling work. Your airplane will be down and your training will be stopped while you wait. You’ll be paying fixed costs (at the $6,400/year rate) while it sits, and sits, and sits… meanwhile, your skills acquired in training will atrophy.

Similarly, many aircraft parts are hard to find and/or have substantial lead times. Note that overhauled engines from Air Power (linked above) are on backorder, with a 6-9 month lead time. If you’re waiting for a part, you’re not training… all the while, the airplane is costing you money.

INSTRUCTION: There’s generally no shortage of independent flight instructors willing to teach in owned airplanes. Nonetheless, prior to acquiring an airplane, make sure you’ve secured an instructor who is willing and capable of teaching in your new airplane. Some instructors (like me) simply don’t fit into, say, a Cessna 150. Others may not be insurable in your airplane.

"Won't I Make Some Money When I Sell It?"

Possibly. General Aviation airplanes are generally perceived to be appreciating assets, much like real estate. Prices have been trending upward since 2011, and prices for Cessna 172-type airplanes have more than doubled in the past 13 years, with most of that increase the past 5 years.

However, that isn’t always the case. The period from 1999 to 2011 saw aircraft as depreciating assets. From 1999 to 2008, values declined slowly, and from 2008 to 2011, that decline picked up momentum, corresponding with the global financial crisis. Had you purchased a Cessna 172M in 2007, it would have lost more than a third of its value by 2011.

Any accidents or incidents can result in diminished value, or even a total loss. Additionally, your aircraft (and engine) will have 200 more hours on it when you go to sell it, so it may not be as appealing to buyers, especially if the engine has exceeded TBO.

More "What Ifs"

Flight training can be interrupted by factors other than airplane maintenance and availability.

MEDICAL: Medical certification is a very common roadblock for new flight training students. Failure of an FAA medical means that you cannot fly an airplane solo, and thus, cannot complete your flight training. Even a deferred decision on an FAA medical can delay flight training for months or years. If you have a denial or deferral of your medical, your airplane will still accrue bills for fixed costs…for however long it takes to get medical clearance. Make sure you’ve secured a medical before even considering buying an airplane! There is also a non-zero risk that you will experience medical issues that cause you to be grounded after your aircraft purchase.

FLIGHT TRAINING APTITUDE, MOTIVATION, and RESOURCES: Flight training is hard! According to one AOPA survey, about 80% of people who start flight training don’t finish it. Regardless of whether you believe the 80% figure, it’s plain that there is a significant drop-out rate in primary flight training.

Many people are surprised by the amount of academic work and studying that is required. Others have challenges finding time to fly. Some discover that after a few lessons, they just don’t like the process of flying as much as they thought they would. It should be obvious that these discoveries are a lot easier to handle if you’ve rented, versus being $100k into an owned airplane.

HANGAR/PARKING AVAILABILITY: You will need a place to park your airplane when you are not flying it. In some parts of the country, hangar space (and even tiedown space) is hard or impossible to find. Wait lists can span years, and costs can be prohibitive. You’ll want to ensure you have a place to park your airplane, especially if you are in a climate where a hangar is necessary.

INSURABILITY: Insurance companies are usually willing to insure standard trainer-type aircraft (Cessna 172, Piper Cherokee series, etc.), even for pilots with zero time. Yes, you’ll pay a higher rate than a certificated pilot initially, but your rates will diminish as you build experience and earn certificates and ratings. However, when you combine a low-time pilot with non-standard aircraft (think: high-performance, tailwheel, etc.), many insurers will refuse to underwrite a policy. Sometimes, they will offer coverage, but at extremely high rates (for example, a student in a high-performance Maule tailwheel may need to pay $10,000 a year for insurance). Make sure you can get insurance at an affordable rate for any airplane you are considering buying!

CHANGING MISSIONS: Many people who purchase aircraft early in their training (especially those looking to save money) will buy the cheapest aircraft they can find. Usually, this means something with significant limitations, like a VFR Cessna 150. It may only cost $35,000, but it can only carry two (small) people, minimal luggage, and it’s slow. For most, this is not going to be a “forever” airplane; they’ll want something more spacious, faster, and/or better equipped as they move on in their flying. Now, they’ll be in the spot of needing to sell the 150 and buy something else… a risky process that takes time and money. Transaction expenses include a pre-purchase inspection by a certificated mechanic, travel costs, escrow fees, broker fees, and so on.

SLOW PROGRESS: If you’re planning a slower flight training journey, the math quickly becomes messy for ownership. Fixed costs are, well, fixed, whether you’re flying 10 or 100 hours a year. Recall that our fixed costs were $6,400 a year for the example airplane ($64/hour for 100 hours of use), and $90/hour for operating expenses, for a tota hourly cost of $154/hour.

Let’s say you are only able to fly 20 hours per year, rather than the 100 you planned. That means $320/hour for fixed costs, and after adding operating costs, each of those 20 hours cost you $410 per tach hour. Yikes! Even at 40 hours a year, the math is still rough with the airplane costing you $250 per tach hour to operate.

That's All Great, but These Things Won't Happen to Me!

To that I say, “may the odds forever be in your favor.”

The reality is that a large number of student pilots don’t complete their training. While I’m sure you think you’ll be the 1 in 5 that finishes their initial certificate, it’s likely that the 4 out of 5 who don’t finish also thought they’d be able to do it as well. After all, we don’t start things like this intending to wash out. Having a large investment in your own training (in the form of an aircraft) may provide motivation to finish, but it can also be a burden if you need to slow down, pause your training, or stop training altogether.

If it’s not clear already by the several pages you’ve just read, the ownership learning curve is steep, and the consequences for not knowing what you’re doing are expensive (both in terms of time and money).

I see far too many airplanes bought by eager students that end up sitting neglected on the ramp collecting dust, because the student had more enthusiasm than sense and rushed into a purchase.

When Can Student Ownership Be a Good Idea?

There are a few circumstances when owning your own airplane for training may be a good idea.

WHEN FINANCES ARE NOT A CONCERN AND YOU KNOW YOUR MISSION: If you are lucky enough to not have to worry about money, it’s possible that buying an airplane to train in may make sense, especially if you have a good idea about what your long-term mission looks like. For example, if you want to buy a Cirrus SR22T so you can fly yourself to business meetings around the Southwest, and you don’t mind the expense of owning and maintaining a Cirrus, there may be advantages to learning from zero in your own aircraft. Yes, it will take longer than in a Cessna 150, and yes, it will be considerably more expensive. However, you can tailor your training to both the aircraft and the mission; for example, practice doing long cross-country flights and making use of all the technology in your aircraft (technology that you won’t find in a Cessna 150).

THERE IS NO FLIGHT SCHOOL OR FBO NEARBY WITH SUITABLE RENTAL AIRCRAFT: If you live in a rural area, it’s possible that there are no flight training operations near you. If accessing a training aircraft would require significant commuting time and expense, it may make sense to buy an airplane, and find a local CFI or hire a CFI to come to you. Another circumstance where you may not be able to find a suitable airplane would be if you were looking to earn a Sport Pilot certificate, but your local schools do not have LSAs for rent.

YOUR AVAILABILITY IS NOT COMPATIBLE WITH RENTAL SCHEDULES: Some aircraft rental services require significant advance notice to schedule airplanes and flight instructors. If you have work/life limitations that do not allow you to plan weeks or months ahead, this may make flight training challenging. if not impossible. If you own your own aircraft, you only have to worry about scheduling the instructor.

YOU HAVE A WAY TO ACQUIRE AN AIRCRAFT FOR LITTLE OR NO MONEY: Occasionally, students will be seeking flight training because they’ve found themselves with a low-barrier path to aircraft ownership. For example, you might inherit an aircraft, or have the opportunity to purchase one at a highly discounted price from a family member. Operating and maintaining that aircraft will not be free, but not having to spend a big chunk of change up front can make a few maintenance events much easier to deal with. If this applies to you, consider if the aircraft is a good fit for your long-term goals. If not, it may make sense to sell the aircraft and put the money toward rental and training (and perhaps a future down payment on another aircraft).

YOU HAVE ACCESS TO FREE OR DISCOUNTED MAINTENANCE: If you (or a friend or family member) are an FAA certificated mechanic and can do all the work required on your own airplane, you’ll save a bundle on maintenance labor. You’re also less likely to accidentally purchase an aircraft that has looming large maintenance expenses assuming you (or they) know what you’re looking for in a pre-purchase inspection.

YOU HAVE ACCESS TO FREE OR DISCOUNTED INSTRUCTION: Most schools and FBOs only allow approved instructors to teach in their airplanes. However, if you have an instructor friend or family member who offers to teach you for free, it may make sense to purchase an airplane for them to teach you in. Make sure you insure your airplane in a way that covers both you and your instructor.

If Not Now, When Does Ownership Make Sense?

In my opinion, the best time to own an airplane is after you’ve earned your initial Private Pilot certificate. At this point in a pilot’s progression, they have shown a commitment to and aptitude for flying.

Waiting a little longer (until after an instrument rating) may still be a wise plan. A pilot with a few hundred hours and a couple of years around aviation will have a better idea of what their mission is, and will better understand what types of aircraft (and what equipment/avoinics in that aircraft) are the best fit for their mission. If they find that low-and-slow flying makes them happiest, then something like a Piper Cub may be an option. On the other hand, if they’re looking to travel cross-country with family, a high-performance retractable gear airplane built for speed and well-equipped for IFR may be a better fit.

The more “experienced” pilot will also have a better idea about how flying fits into their lives. If they anticipate flying 100+ hours a year for the foreseeable future, ownership starts to make financial sense, on top of having access to the airplane 24/7/365.

Remember, too, that ownership doesn’t have to be sole ownership. Partnerships and clubs can offer aircraft access comparable to sole ownership, at a lower price point. AOPA has a wonderful guide on co-ownership here: AOPA Pilot’s Guide to Co-Ownership.